Capital in Difficult Places - Accelerating Catalytic Climate Philanthropy

Distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen,

Good morning.

We use certain adjectives quite liberally these days – game changing, needle-moving, transformative. Philanthropy alone is not enough; we also want this to be catalytic.

The concept of a catalyst was first introduced by the Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius in the early 19th century. He used the term “katalysis” to describe the acceleration of chemical reactions by substances that he called “catalysts” [0] .

The term “catalytic philanthropy” first appeared in an article in the Standard Social Innovation Review in 2009 and was described as the approach practised by innovative funders to create transformative change beyond writing a cheque. These funders were observed to practise strategic giving, using an expanded toolkit that went beyond the donations and grants commonly associated with traditional philanthropy. Like a good, strong chemical catalyst, these philanthropists broke down barriers and accelerated change.

The focus of today’s forum on catalytic philanthropy is well-timed as we are indeed seeing promising signs of being on the cusp of a new age of philanthropy. We are moving from the era of Wealth 1.0, led by a generation driven by wealth creation and preservation, to the age of Wealth 2.0. This younger generation of wealth owners has a strong desire to direct wealth for good and seeks to shape change that is meaningful and has impact.

Catalytic philanthropy is particularly relevant and critical for the climate agenda. Climate change is the fundamental challenge of our times, and the decisions and actions we take today will have far-reaching implications for future well-being and indeed, survival.

- This urgency is clear from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) AR6 Synthesis Report, which points to a “rapidly closing window of opportunity” to keep to the 1.5˚C temperature target [0] .

Damage has already been done.

- The past eight years have been the eight warmest on record and surface temperatures in 2022 were 1.1 to 1.3˚C warmer than pre-industrial periods [0] .

- Global mean sea levels have risen approximately 210 – 240mm since 1880, and the annual increase is currently about 3mm a year [0] . According to NASA estimates, in over a decade and a half from around 2005 to 2021, Antarctica and Greenland lost enough ice to fill Lake Michigan, which is equivalent in size to 80 Singapores.

- The Bramble Cay melomys was the first mammal reported in 2019 to have gone extinct as a direct result of its habitat being destroyed by rising sea levels. [0] More than 10,000 other species are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species and face increased likelihood of extinction as a result of climate change [0] .

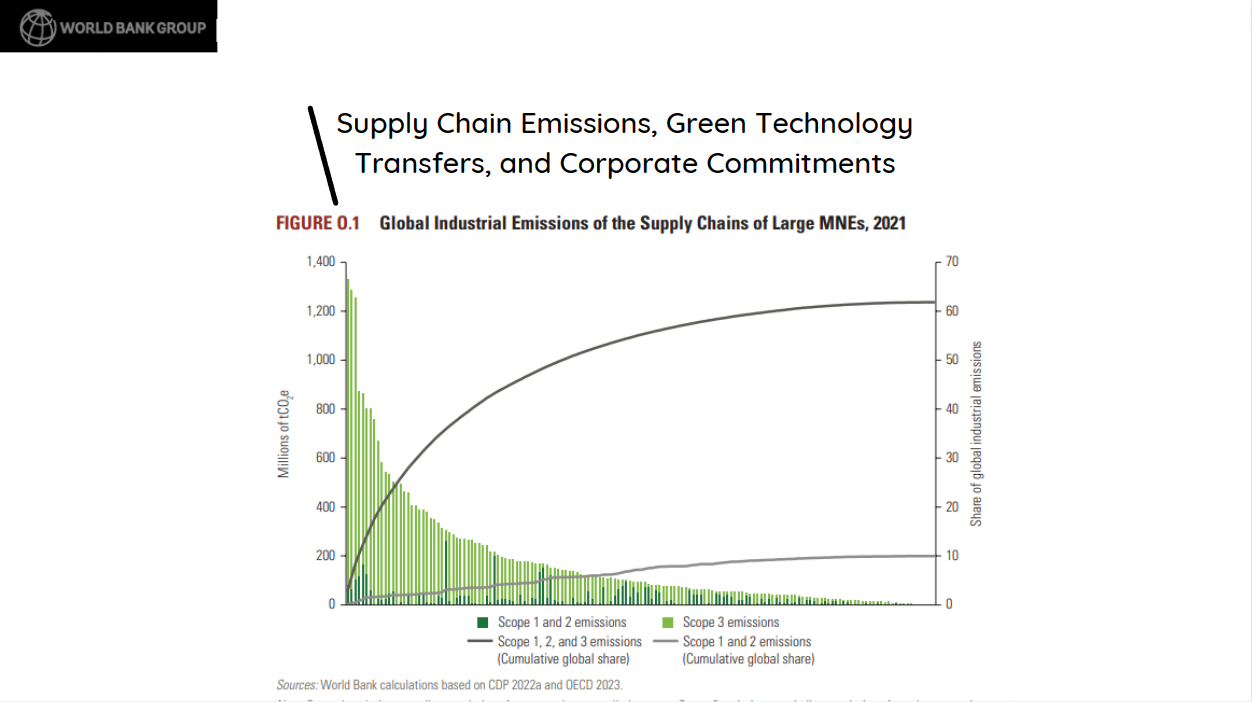

Despite the urgency of the climate challenge, the world is investing nowhere near what is required to get to net zero by 2050.

- According to McKinsey, achieving net zero by 2050 would require about US$9.2 trillion of investment per year over the next 30 years, but only about US$5.7 trillion per year is being invested today. We are about 35% short of what we need each year [0] .

- Closer to home, within Southeast Asia, we need US$1-US$3 trillion in investments to close the emission gap by 2030, but the current investment level is less than US$20 billion [0] .

There are many reasons for this investment gap, including certain knowledge and capability gaps, but this is primarily a problem of risk. There are three key dimensions to this.

First, the key barrier to capital flows is when returns are often not viewed as proportionate with the level of perceived risks. Investors are skittish about country risk, credit risk and project risk. This is especially the case in emerging markets, where investment environments are viewed as more challenging. Yet these countries are also where capital is most badly needed for sustainable infrastructure and development.

The second issue is that some climate technology is nascent, which adds further risk to the picture. We have seen this in investment patterns in carbon capture and storage technologies, which could account for one-third of the emissions reduction required to meet the net zero target by 2050 [0] . The International Energy Agency has estimated that the cost of building sufficient carbon capture and storage facilities to reach net zero targets will be between US$655 billion and US$1.28 trillion [0] . While investments into carbon capture and storage projects reached a record high of US$6.4 billion last year [0] , the sector still requires significant investments. And funding gaps still exist for the research and development of new, more cost-and energy-efficient techniques and solvents of carbon removal, which can be implemented or put to use at scale [0] .

The third dimension is that a number of players with private commercial capital to deploy cannot invest in developmental projects that are below their risk-return profiles, even if they wanted to, due to fiduciary duties and constrained mandates.

What is clear is that traditional models are just not working fast enough to get capital where it needs to go. We need new models, a new paradigm. We need a fresh approach which can lower the hurdle for blended finance solutions and can crowd in private capital to be deployed widely in this region.

This is where philanthropic capital can play a catalytic role. Philanthropic capital is more versatile and can potentially be more flexible, risk tolerant and patient.

- If philanthropic capital takes the form of concessional investments, and we combine this with technical assistance, political risk covers and even local currency hedging solutions, philanthropic capital can crowd in commercial capital that is many multiples of the concessional slice.

- Philanthropic money has a tough job – like Captain Kirk in Star Trek, it needs to boldly go where no other capital has gone before. It needs to go to the most difficult places and to challenging, marginally bankable projects.

- Provided philanthropic capital is prepared to be deployed strategically, we can enhance the impact of philanthropic resources by using these resources in targeted blended finance solutions to tap into the many trillions of private capital seeking bankable deployment opportunities.

Unlike Star Trek, this is not science fiction. There is now enough evidence that certain models and pilots have worked.

This should give us confidence about the powerful impact philanthropic contributions can have in the climate arena.

- One example is the Climate Innovation and Development Fund which supports sustainable and low carbon projects, including electric mass mobility solutions, in South and Southeast Asia. With a US$25m grant commitment from Bloomberg Philanthropies and Goldman Sachs, the fund will leverage up to US$500m in additional financing. One of the fund’s investments was to develop an electric bus fleet and an electric vehicle charging network for Vietnam – this mobilised investment capital that was 44 times what the fund put into the projects [0] .

Another positive development is that philanthropic organisations now have a broad range of funding mechanisms to choose from. These include:

Outright grants that defray the cost of feasibility studies and proof of concepts, thereby reducing the risk of investing in such early-stage projects;

Guarantees which reduces the risk to investors by taking on the liabilities in the event that a creditor defaults;

Submarket debt or equity, such as accepting lower returns or absorbing losses first, to make the project more investable by private investors; and

Venture philanthropy that can be invested alongside private capital in projects with longer investment cycles.

We have a range of tools, we have successful examples and models to build off, and we have an urgent challenge.

However, despite this, and despite the fact that we are seeing some US$800bn of philanthropic giving per year, less than 2% of this goes to climate mitigation [0] .

- This can be largely attributed to the complexity and scale of climate issues, a sense perhaps that we are figuratively and literally boiling the ocean, and nothing any of us can do will make a difference.

- There is also increasing awareness of the finite pool of philanthropic money available, as compared to the sheer scale of the challenge at hand. And with that has come increased emphasis on maximising the impact of giving. Family offices are placing greater importance on evidence-based giving and being able to track and measure specific outcomes of their philanthropic dollar. We are seeing increasing demand for standardised impact metrics and platforms that aggregate data and impact benchmarks so that the impact of different projects can be assessed and compared.

What is the way forward? As philanthropists ponder their involvement in the climate imperative, there are three questions that I think could be helpful to frame the issue – Why should I start? How should I start? Who should start?

Allow me to elaborate on the first question – why should I start? Specifically, why should I start giving to climate?

Philanthropy is personal - and philanthropists feel a deep sense of personal responsibility and ownership towards specific causes they support. Globally [0] and regionally [0] , top focus areas continue to be in education, health care and poverty alleviation. These are areas that are widely regarded as fundamental issues that affect basic human needs.

However, there needs to be greater awareness and acknowledgement that the effects of climate change will underpin all aspects of human health and well-being, and Asia will be one of the hardest hit regions.

- Globally, between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year due to heat, diarrhoea, malaria, and childhood undernutrition [0] .

- Research by the McKinsey Global Institute has found that Asia’s least developed countries face the greatest climate risk, and estimates that climate change will reduce working hours in poorer countries by up to 15% [0] . In Asia, countries like India, Bangladesh and Pakistan are most vulnerable, given that they have labour-intensive economic sectors. The increasing intensity of heat waves have already made outdoor labour more challenging, and projections show that outdoor labour will become extremely difficult, with significant impact on GDP [0] .

- The grave importance of channelling resources to tackle climate mitigation and adaptation is therefore clear. Why should we start? Because if we do not, the implications to health and well-being are unthinkable and severe.

Let me turn to the second question – how should I start?

It can be daunting to embark on climate funding. There are a vast number of sectors that we need to prioritise – from renewable energy to carbon capture, energy efficiency to food security. There can seem to be an endless array of new developments, concepts and acronyms to keep track of and learn – taxonomies, standards, the latest greenwashing allegations, and the list goes on.

Even more importantly, philanthropists want their dollar to count and want to know which areas they should channel their contributions such that there can be maximum impact. Is this in supporting affected communities and the other just transition aspects of the early phase-out of coal? Or is this in nature-based solutions?

Given this, the first step must be to build greater awareness on climate needs, solutions and available projects.

Collaboration is key in allowing for the exchange of expertise, experience and best practices. Philanthropists can learn from one another and apply these lessons to their own climate strategies. This underscores the importance of platforms such as the Impact Philanthropy Partnership (IPP) that seek to educate and encourage thought-provoking conversations. Events like today’s forum and other events in the IPP series will bring together both the Committed and the Curious and catalyse awareness and action.

Training and capacity building also play an important role to deepen the level of understanding on this topic. WMI has contributed to this effort, having trained 350 learners in philanthropy and ESG topics since just last year. I was excited to learn that WMI will be launching programmes in impact investing and other topics progressively over the next 12 months and I would like to encourage you to approach WMI to find out more.

This takes us to the final question – who should start?

This is perhaps the most important question and requires the largest mindset shift. The scale of the climate challenge will require the expertise and resources of all stakeholders in the ecosystem. What is needed is collective action across the private sector, the philanthropy sector, the public sector and the people sector. Everyone is going to have to do more.

The public sector needs to be an enabler that provides a facilitative environment for philanthropy and sustainable finance to flourish and encourages all stakeholders to play their part. On facilitating the channelling of wealth for purpose specifically, the MAS and various government agencies are working on a number of initiatives. Let me share two of these.

The first is the S$5m Asia Climate Solutions (ACS) design grant hosted by Convergence which was launched at the 8th Singapore-Australia Annual Leaders’ Meeting last week. This will provide grant funding for proof of concepts of innovative and scalable blended finance solutions to fund sustainability projects. The design grant has received support from UBS Optimus Foundation, Olayan, the Australia Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and MAS, and is now open for its first call for proposals. The ACS design grant still has room to grow, and we welcome anyone interested in participating as a donor to step forward and join us.

The second is the Philanthropy Tax Incentive Scheme which was announced in Budget 2023. This is for donors with Family Offices managing Section 13O or U funds in Singapore. Under the scheme, qualifying donors can claim 100% tax deduction for overseas donations made through qualifying local intermediaries, capped at 40% of the donor’s statutory income.

- There are three possible categories of qualifying donors – the donor could be the Single-Family Office in Singapore; the ultimate beneficial owner or beneficiary of the Section 13O or 13U fund managed by the family office, or a related family business operating in Singapore.

- The scheme will go live on 1 January 2024 and run until 31 December 2028. Successful applicants will be granted the award for a period of 5 years from their incentive commencement date.

- Given that the scale of fighting climate change necessitates collective effort across domestic-borders, we hope that this new scheme will be helpful in encouraging more giving to climate-related causes from Singapore.

I have spoken at length about how the philanthropy sector can play a critical role to catalyse commercial investments. We certainly hope that those of you in the audience who are able to step forward and contribute will do so.

The private sector also has an important role to play. For example, financial institutions, as stewards of capital, have the ability to exert influence over client behaviour, through client engagement on transition strategies or the structuring of innovative climate financing solutions.

It is heartening to see that the industry has been stepping up to do their part.

- For example, last October, the Private Banking Industry Group (PBIG) Sustainability Taskforce, in consultation with the Institute of Banking and Finance Singapore (IBF) and the MAS, launched a common industry training benchmark to upskill private banking relationship managers in the area of sustainability.

- Private banks represented on the PBIG Executive Committee also committed to completing the recommended training within three years or earlier. This will enhance competencies across the board, and better enable financial institutions to advise their clients on transition and sustainable investment approaches.

As I conclude my remarks, I wanted to share with you a quote by the American philosopher and historian, William James. He said, “The greatest use of a life is to spend it on something that will outlast it.” This is the climate story through and through. The actions we take today will shape the lives of many generations that come after us. This is a worthy endeavour, an endeavour that we badly need to succeed, and which absolutely needs to be both bold and catalytic.

***

- [1] Jaime Wisniak (2018), “The History of Catalysis. From the Beginning to Nobel Prizes.”

- [2] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2023), “AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023”.

- [3] Carbon Brief (2023), “State of the climate: How the world warmed in 2022”.

- [4] Climate Change Knowledge Portal – World Bank Group (2023).

- [5] National Geographic (2019), “First mammal species recognised as extinct due to climate change”.

- [6] IUCN (2019), “Species and climate change” Issues Brief

- [7] McKinsey & Company (2022), “The net-zero transition – What it would cost, what it could bring”.

- [8] Bain and Temasek, with contributions from Microsoft (2022), “Southeast Asia’s Green Economy 2022 Report”.

- [9] Forbes (2021), “How To Scale Up Carbon Capture And Storage”.

- [10] Global CCS Institute (2021), “Global Status of CCS 2021”.

- [11] BloombergNEF (2023), “Carbon Capture Investment Hits Record High of $6.4 Billion”.

- [12] M&G Investments (2023), “Carbon capture and storage: Feasible, effective and investible?”.

- [13] Goldman Sachs (2022), “Bloomberg Philanthropies and Goldman Sachs Backed Climate Innovation and Development Fund Announce its First Blended-Finance Investments”.

- [14] ClimateWorks Foundation (2021), “Funding trends 2021: Climate change mitigation philanthropy”.

- [15] WealthX (2019), “Trends in UHNW Giving 2019”, UBS (2018), Global Philanthropy Report.

- [16] UBS-INSEAD (2011), ”UBS-INSEAD Study on Family Philanthropy in Asia”, UBS (2018), Global Philanthropy Report.

- [17] World Health Organization (2023), “Climate change”.

- [18] McKinsey & Company (2021), “It’s time for philanthropy to set up the fight against climate change”.

- [19] McKinsey & Company (2020), “Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts”.

First, please LoginComment After ~