Why foreign direct investment is needed to fulfil the climate justice agenda?

The climate justice agenda is extensive. One of its priorities is helping countries that have contributed least to climate change but suffer most from it. Progress on this issue was the headline achievement at the UN Climate COP27 last November, where developed countries agreed to launch a loss-and-damage fund for the most vulnerable nations.

Looking ahead, the climate justice agenda must include stepped-up collaboration to fund greener development in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs). Investment in the trillions is needed and well worth making. A just transition in these countries will benefit the whole world by keeping climate goals intact and narrowing an economically and socially dangerous north-south gap as global decarbonisation accelerates.

COP27 showed progress here, but it’s still early days. To achieve the necessary scale, collaboration requires new commitments from developed countries and EMDEs, innovations from development finance institutions and multilateral development banks and multiple types of capital, some of it public but most of it private.

Why FDI matters so much

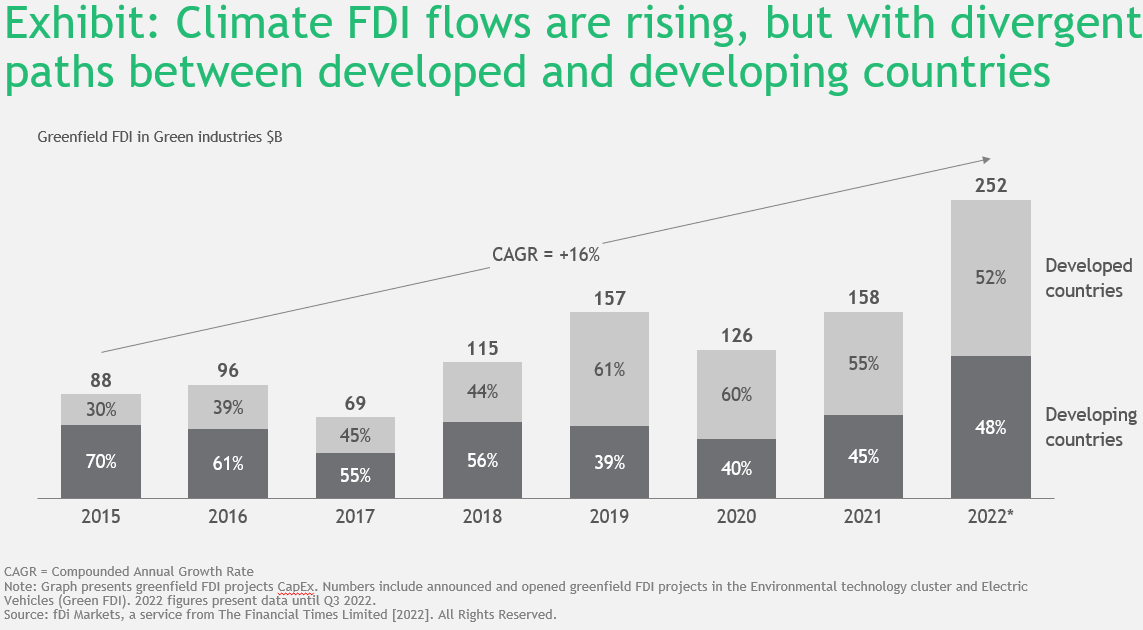

Foreign direct investment (FDI) across the many sectors impacting or impacted by climate change — 'climate FDI' for short — is the most important segment of these much-needed private capital flows. Relevant sectors range from agriculture, food and forestry to energy and infrastructure and tracking investment flows across them is difficult. However, using a simplified definition focused on renewable energy, transportation and environmental technology and services, data from fDi Markets, illustrated in the Exhibit below, shows that climate FDI has tripled in the last ten years and is now the largest FDI category.

In developed countries, strong flows of climate FDI have supplemented large pools of domestic capital in financing the transition, a dynamic that green incentives in the US Inflation Reduction Act will accelerate.

But few EMDE countries have received a significant share of climate FDI. Indeed, underperformance in channelling climate FDI is a key reason why developed countries haven’t mobilised the $100 billion in annual flows of public and private finance they pledged in 2009 to support climate action in the developing world.

Changing this picture is an urgent task. EMDEs face the transition with limited financial resources and, in many cases, post-COVID-19 pandemic high debt levels and/or regulatory barriers to investment. Many come with less than glowing sovereign credit ratings. With some notable exceptions, EMDEs have made less progress in greening their economies.

For now, most make only a small per capita contribution to global emissions. But a significant share of future growth in energy use will be driven by EMDE countries as they improve living standards for their populations. If they cannot decouple economic growth from greenhouse gas emissions, the climate challenge becomes even more daunting.

What the early movers have accomplished

With sufficient investment, this scenario can be replaced by a much more positive one. The logic of falling costs for clean energy sources and steady improvements in related technologies holds true wherever those sources are found. And, while fossil resources are concentrated in relatively few countries, renewable resources are more widespread, though development relies on stable technology supply chains.

Some early movers in the developing world already benefit from significant climate FDI. Chile, for example, is enjoying the results of a pivot to renewable energy that began in the 2000s. Climate FDI inflows of $ 17.4 billion over the past five years have helped transform its energy sector, which in 2022 remarkably produced more electricity with solar and wind power than with coal for the first time.

Indonesia’s large automotive sector has helped it attract $17.3 billion in climate FDI as the global industry turns to electric vehicles (EV). The country opened its first EV factory in 2022 and believes that its big domestic market can help it compete with India and other early movers in manufacturing two- and four-wheel EVs.

EMDE countries have also seen major inflows from the nascent green hydrogen industry. Disruptions in oil and gas markets, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have further boosted enthusiasm for this energy carrier, considered the likeliest successor to fossil fuels in heavy industry.

Morocco — like Chile, an early deployer of renewable power and an expected future hydrogen leader — is attracting FDI to position itself as a major exporter of both green hydrogen and electricity generated from its solar and wind resources. Egypt, host of COP27, marked the occasion by announcing framework agreements for no fewer than eight, multi-billion-dollar green hydrogen projects.

Accelerating the flows

Collaboration to mobilise climate FDI in the developing world is already underway. The challenge now is to accelerate it. Development finance institutions and multilateral development banks have partnered with the OECD and others to support much of the activity above, as well as initiatives, such as a trio of Just Energy Transition Partnerships with South Africa, Indonesia and Vietnam. The MDBs have also upped their commitments to climate finance, though they haven’t yet fully aligned their financial flows with the objectives of the Paris agreement, as they pledged in 2017.

But much more is required. An important step would be a common definition of climate FDI, to facilitate collaboration and tracking of flows and combat potential greenwashing. The Bridgetown Initiative, led by Barbadian prime minister Mia Mottley and backed by French president Emmanuel Macron, envisions a comprehensive overhaul of the multilateral system to unlock urgently needed climate finance.

Even with more help, EMDEs will face many challenges in navigating the transition. How can they meet them? They are a highly varied group, so there is no single set of levers for them to pull. But there are some important lessons to be learned from these early movers — starting with the power of setting ambitious climate goals and supporting them with investment facilitation measures, including regulations that are predictable, stable and transparent.

When it comes to export-oriented projects, such as green hydrogen, many countries are also taking care to avoid simply becoming exporters of a new commodity, planning instead to use future capabilities to climb the value chain, boost low-carbon domestic industry and add quality jobs at home.

There is much work ahead. Mitigation projects, such as renewable power development, are better at producing revenues and hence attracting FDI, than adaptation projects, such as building seawalls or combating deforestation, yet the needs in EMDEs are significant on the adaptation side.

Encouragingly, innovations such as the African Carbon Markets Initiative, launched at COP27, are showing a way forward on problems such as deforestation. And the climate FDI dialogue continued in a session gathering business leaders and policymakers at Davos in January 2023. Attendees learned that harnessing climate FDI is already a top agenda item for most EMDE investment promotion agencies and that they are working on appropriate incentives, regulations and enabling environments.

The discussion also showed how the distributed value chains for many green projects make international cooperation more rewarding than competition. A G20 Minister highlighted that climate FDI is valuable not only for environmental reasons but also for fostering communities and creating future jobs in developed economies and EMDEs.

The so-called north-south divide on climate reflects deeply felt differences, but there’s little doubt that these differences can and must be bridged for the well-being of people in developing and developed countries alike. Stronger flows of climate FDI into EMDE countries will help achieve this.

First, please LoginComment After ~